Colonial Horrors

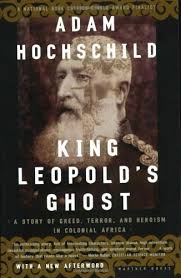

King Leopold’s Ghost is a work of popular history about the horrors of Belgian colonization in the Congo. Written by Adam Hochschild, it was a surprise best seller when first published in 1999. It has it since been reprinted many times, made into a movie, and reached a broad audience across the world. It has legs, traction, and intellectual and moral heft. But it was not a book on my shelf. I recently addressed its absence.

King Leopold’s Ghost is a work of popular history about the horrors of Belgian colonization in the Congo. Written by Adam Hochschild, it was a surprise best seller when first published in 1999. It has it since been reprinted many times, made into a movie, and reached a broad audience across the world. It has legs, traction, and intellectual and moral heft. But it was not a book on my shelf. I recently addressed its absence.

Reading it was well worth the time. It recounts a humbling history of greed, intrigue, and the evils of colonial imperialism, tempered with real courage in African and from a growing human rights movement. I should have read it earlier. Ignorance is no excuse for continued ignorance.

Hochschild’s book is based mostly on the work of other historians. What makes his account special is that he weaves them together into a compelling narrative. It is well-paced, historically accurate (Hochschild is professional and generous in acknowledging others’ efforts), and deeply distressing. While the latter part of the nineteenth century in Europe can be romanticized as a period of growing urbanization and sophistication, much of the economy was driven by forced labor and wanton cruelty. Tens of millions of African people were caught in an exploitative system that killed at least ten million and tortured more. It was, in many ways, a training ground for the wide scale horrors of the twentieth century.

Textbooks often describe the rush of economically developed countries in Europe and North America to find natural resources around the world as a rational expression of market demand. If a growing industry needs rubber, then rubber must be found, harvested and transported. Missing is an understanding of the impact on people and cultures. King Leopold’s Ghost makes clear that Belgium’s exploitation of the Congo region was not about market forces. It was driven by the machinations of an evil and rapacious leader, King Leopold, who bribed, lied, and politicked to gain personal wealth and power. He built an hypocritical propaganda machine, selling the world a story of development and protection while actually doing the exact opposite.

A few recognized what was happening and tried to stop it. Hochschild puts Edmund Morel, who led the global human rights campaign to end Leopold’s rule, in a place of prominence. Roger Casement, later embroiled in the Irish independence movement, was his partner. An African-American historian, soldier, lawyer and activist, George Washington Williams, was in the Congo earlier and tried to warn the world. William Henry Sheppard, a missionary, documented the atrocities and was one of the few to record the testimony of the indigenous people. Joseph Conrad, of course, is also part of the story. He traveled the Congo River and as it turns out, A Heart of Darkness was not as much a work of imagination than a reflection or a terribly reality. Many others are part of the broader narrative, from the famous explorer Henry Morton Stanley, to Mark Twain. Twain wrote a scathing satirical pamphlet, King Leopold’s Soliloquy, which helped bring global attention to the evils of Belgium’s King and colony.

King Leopold’s Ghost is a sobering book. It is and will remain a vital reminder to engage, question, and work for human rights.

David Potash