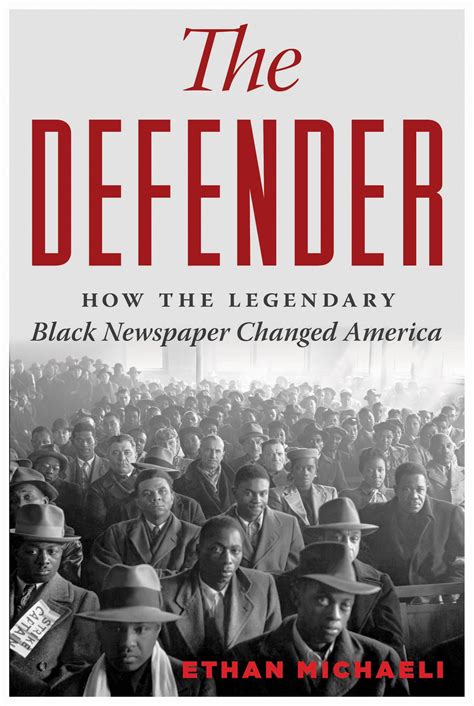

The Defender: A Powerful Voice for Black Americans

The story of Chicago’s The Defender, perhaps America’s preeminent Black newspaper of the 20th century, is the history of race and racism in the city and the nation. It’s been an extraordinarily important publication, an essential voice for Black community and a tireless advocate for racial justice and agency, for over a century. Ethan Michaeli’s hefty book, The Defender: How The Legendary Black Newspaper Changed America, is a sprawling account of the newspaper, strong on personalities and affection. It is tome at 633 pages, yet is still leaves at least this reader with questions. More than a history of a business, Micheali’s volume shines a provocative light on the intersection of The Defender, those that made it, the stories that it told, and the communities in which it was read.

The Defender was the brain child of Robert Abbott, a fascinating Black entrepreneur from Georgia who visited Chicago’s 1893 World Colombian Exposition as a young man. Among his many skills, he was a talented singer and a member of the Hampton Quartet. Abbott, impressed with the city’s Black professionals and keen on the opportunities he saw in the growing metropolis, decided to move to Chicago and become a lawyer. Plans changed as Abbott’s law career did not take off as expected. Knowing a bit about printing from a relative, Abbott judged that the city’s growing Black community needed a newspaper. Borrowing money and leaning on friends and acquaintances, he started The Defender in 1905 with an initial print run of 300. His offices were in his landlady’s dining room. The paper, with a mission as a defender of Abbott’s race, was truly a visionary enterprise. From those small steps, Abbott’s drive, brilliance and amazing work built the organization and a paper with international impact.

Initially read on the South Side of Chicago, The Defender was passed from reader to reader. Importantly, the newspaper was picked up by Pullman porters, many of whom lived or traveled through Chicago, increasing its scope. Over time, Abbott attracted a cadre outstanding journalists and writers, like Ida B. Wells and Langston Hughes. The paper was tireless in its attention to racism, opportunity and justice. It was relentless in its descriptions and criticisms of lynchings and other injustices, especially in the South. The paper investigated and reported factually racist atrocities and lynchings, in direct contrast to what white publications printed. Abbott and members of the papers were harassed and threatened, but they pressed on, unfazed. The paper’s work accelerated the political and cultural organizations of within Black Chicago, and was an extraordinarily important factor in the Great Migration. Abbott and the paper initiated the Bud Billiken parade in 1929, a celebration that has grown to being the nation’s largest African-American parade. It is a wonderful August event, and Michaeli cleverly draws the reader into his work by opening with a young Barack Obama at the event.

John H. Sengstacke, Abbott’s nephew, took over the paper in 1940 followings Abbott’s death. The Defender played a key role in politics and race issues at the city, state and national level through World War II, pushing hard for civil rights and the integration of the military. Facing strong competition from other Black newspaper by this time, Defender journalists and editors were prominent and active. That key scope extended through the 1950s and the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s and beyond. Political and cultural leaders needed the newspaper’s attention, especially as more Blacks voted and acquired wealth and influence. It is difficult to overstate the key role that The Defender served in keeping Black communities informed and engaged.

Michaeli’s book describes all of this very well. He’s a talented writer with a good eye for detail. Consistently using the paper as a primary source, he has rich material to engage the reader. And as The Defender was active across the continent for decades, there’s more than enough history to reference and recount. Michaeli’s attention to the violence and prejudice that The Defender covered very strong. He appreciates, as did the newspaper’s staff and readership, the harsh realities of Black Americans. He underscores, too, that racial justice was only achieved through suffering and struggle. The book offers a powerful reminder of just how constant racial bigotry and violence were a prominent throughout the twentieth century.

On the other hand, the lengthy book could have been more effective with greater attention to context and history. Michaeli does reference some of the important historical scholarship that helps to explain the big picture, but I did not come away with the sense that he was comfortable crafting his history in that realm. I understand that this would have changed the book. Nonetheless, for those not familiar with twentieth century American history, or the history of Chicago, The Defender moves quickly and makes assumptions. Some of this is simply how the author approached the material. Michaeli, a white University of Chicago English major, took a job as a copy editor at the Defender a year after graduation in 1991. He stayed at the paper for five years, working his way up to journalist, and learning about Chicago, racism, and American history along the way. Five hundred pages into the book – its structure is chronological – Michaeli introduces himself, writes about his ignorance of race and history, and explains his journey to understanding through his job and the work of the newspaper. As he notes, the experience “filled in so many blanks in American history left by the textbooks of my youth and showed me how things really work.”

At the start of the 1900s, America had more than 20,000 newspapers. Many of these publications represented communities ignored by mainstream presses. Their function was much more than reporting the news. These newspapers were critical in the development of group identity and political mobilization, particularly as the country wrestled with issues of suffrage, political participation, and the meaning of being an American. Now read mostly by graduate students, the vast majority of these papers have long been assigned to archives, their readership and influence waning over the decades. The Defender had a much greater impact than most and has lasted longer than most. It still exists online and still has an important voice. Michaeli’s book goes far in telling that story.

David Potash