Rethinking Attica and the Carceral Imperative

The 1971 Attica prison riot lives in collective culture as a violent event during a period of historical civil unrest. It is a call out in history text books and a reference in studies of America’s criminal justice system. Details of what actually happened, though, are far from well known. As the years add up, fewer are aware of what transpired and why. Pay attention, look more closely, and understanding Attica explains a great deal about America, its political history, and the power of government to shape a narrative.

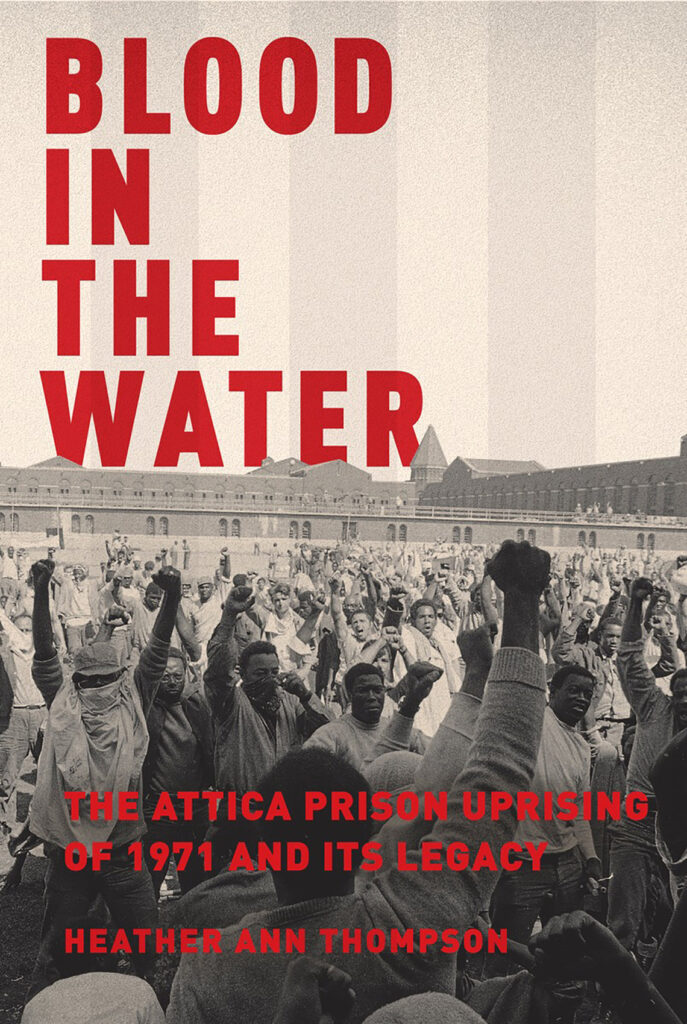

To make sense of Attica, historian Heather Ann Thompson devoted more than a decade to research, filing numerous Freedom of Information Requests and challenging New York State and other government entities for records. With perseverance and luck (her words), she found all manner of material. With great skill and insight, she wrote the uprising’s definitive history: Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. It is truly an outstanding work, well worthy of its many accolades and awards.

The Attica State Correctional Facility is located in Erie County, New York, not far from Buffalo. In 1971, as today, many of its inmates are people of color from the New York City area. Erie County is primarily White. Thompson sketches this out effectively, along with the rebellions of prisoners across the country in the period. Conditions in many prisons were deplorable, with inmates housed in outdated facilities designed for far fewer people. Prisoners sought changes that might bring them basic decencies. Their requests were often met with retribution, violence and disdain. The problem was nationwide and linked by many to broader questions of civil rights and justice.

Thompson addresses the budding tensions fairly, as one might analyze a labor conflict. She explains, expands, and teases out the nuance that is woven into change, resistance, and negotiation and/or resolution. We meet prison officials, prisoners, and numerous figures involved in the criminal justice system in New York State. The riot, or takeover of part of the prison, happens almost accidentally. There was initial violence, with a guard severely beaten (he later dies of his wounds), a prisoner murdered, rape and other terrible trauma. Surprisingly quickly, however, leadership among the inmates took hold. The inmates organized and began to think about their situation and requests. Their prisoners – guards – were protected. In a fluid situation, leadership among the prisoners sought stability and some relief. The inmates negotiated, seeking protections and greater opportunities, such as competent medical care. Elected and civil officials from around the country made their way to Attica. It was a major news story and a flashpoint for race, law and order.

NYS Governor Nelson Rockefeller, ambitious for the presidency and publicly supported by President Richard Nixon, decided to end negotiations. He ordered NYS police and others retake the prison by force. Hundreds of criminal justice professionals, armed to the teeth, stormed the prison and began shooting everywhere. They killed 39 people, hostages and prisoners, and wounded hundreds more. The prisoners were not armed. It was a naked display of power.

Government officials lied and/misled about the nature of the attacks, the violence, and what was transpiring in the prison. Worse still, as the prison fell under official control, wounded inmates were beaten, tortured and denied medical care. Thompson provides chilling details of the violence, which was truly terrible. It was also not initially reported to the public. Much of what happened took many years and court cases to emerge. Many records remained sealed to this day. In brief, Attica was a bloodbath, a site of racist violent retribution of government officials against prisoners. The weeks following the Attica uprising were horrific for the inmates. “Blood in the Water” is an apt title for the book.

The story does not end in 1971, though, for the state worked hard to prosecute prisoners involved in the riot. Thompson tracks the court cases, the multiple investigations, and the four-decade plus push for accountability. She documents how police and other state officials murdered and tortured inmates and then covered up crimes. The details of Attica emerged slowly, report by report and case by case. Lawyers, both for the state and the prisoners, devoted their professional careers to cases both holding prisoners and officials accountable. So, too, did coroners, prison officials and many others involved. Ultimately, no government official was ever held responsible for the deaths in retaking the prison or the following deplorable behavior of prison officials.

Thompson brings the history into a full circle through investigation of the lives of the guards and their families. Families of guards killed during the retaking of the prison struggled to find justice and support. Over time, many found connections with the inmates. The entire hisstory calls into question what justice might or could mean.

Thompson raises so many questions. Blood in the Water is more than a moment in history; it is a study of how broader societal trends in law, crime, and criminal justice intersect with civil unrest, political ambition, and the tremendous power of the state.

David Potash