Martial Mindset: Bush’s War Cabinet

James Mann is a journalist and author. An expert on American foreign policy, he does his research thoroughly and writes with clarity. One of Mann’s strengths is that he knows how to build a narrative with direction and surety. Read his works and one comes away with a real sense of learning something.

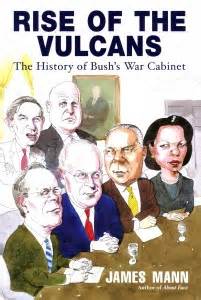

Rise of the Vulcans: The History of Bush’s War Cabinet is Mann’s best-known book. Published in 2004, it straddles the boundary between journalism and history. It was a best-seller for good reasons. Mann tells the history of the six key figures in President Bush’s war cabinet: Vice President Cheney, Secretary of State Powell, Deputy Secretary of State Armitage, Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld, Deputy Secretary of Defense Wolfowitz, and National Security Advisor Rice. Collectively, these well-known leaders helped to guide Bush and America into the invasion of Iraq. Understanding the team, their backgrounds and values, goes far in explicating the Republican foreign policy establishment. That goal – explication of them and how they thought – is the goal of Mann’s book. It is not an examination of how and why the US made the decision to invade.

The book spans more than three decades. We learn of the figures’ childhoods, education, and their rise to influence. As one might expect, amid the diversity of backgrounds there were multiple alignments and affiliations. One of Mann’s skills is teasing out those connections, something akin to backwards looking analysis. The book makes clear how the right background, ambition, and ability to skillfully play the Washington “game” of power could situate one in a position of privilege. Mann’s study likewise illustrates how the wrong choice, the wrong move, or simply bad luck could derail or delay a career. For each of the six, success was neither instantaneous nor assured. Each took different paths to secure a spot in history.

Mann sees the Bush group as representing both Cold War and post-Cold War thinking. He rightly stresses the prevalence of military thinking to the group. They had outsize faith in military solutions, regardless of the source of the issue. Accordingly, the group consistently advanced a military-first mindset, shaping policy and American priorities. Their influence spanned decades and remains a vital strand of thinking. The nickname “Vulcan” was self-assigned. The group believed that they were forging a military machine that would protect and advance US interests. Interestingly, that outsize belief may have been one of the reasons that they were chosen to be in Bush’s cabinet. Criticized for his lack of foreign policy bono fides, Bush intentionally sought out cabinet members that would burnish his reputation.

The traits that all shared, that seem to have pervaded the Bush establishment, included confidence, optimism that America was in the right (if only be default), and that American knowledge, values and problem-solving would eventual prevail in any situation. Mann is very effective in demonstrating how their confidence emerged, was rewarded and reinforced. We know more today about the missteps, the assumptions, and the outright errors of the Bush team. Mann, writing at the time, was able to forecast the strengths and weaknesses that could lead to all manner of consequences, good and bad.

Entertaining, illuminating and disheartening. Rise of the Vulcans remains a relevant book. One of Mann’s strengths is his ability to know how to explain while remaining disciplined. He does not pretend to explain broad historical movements. Nor is this a study of causality. Rather, the book humanizes political leadership and group think, something we would be well-served to always keep in mind.

David Potash