The Sharp Edge of Comedy

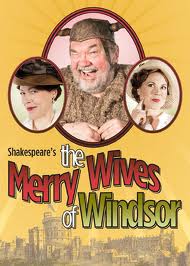

My son and I recently saw the Chicago’s Shakespeare’s Theatre’s production of The Merry Wives of Windsor. I prepared by looking online and reviewing the plot (confessions of a former English major). Merry Wives is not produced all that often and I learned that critics tend to rank it as one of Shakespeare’s weaker plays. The story is an ironic look at relationships, love, fidelity, and ego, with disguises and mistaken identities. It is well suited for an opera with the wives perhaps more wise than jolly. Throw in a fat, aging, and cynical protagonist – Sir John Falstaff – and the play has a bit of a play on itself.

The Chicago production is set in post-WWII small-town England, with musical interludes and lots of antics. Think of Benny Hill doing Shakespeare. The play moves quickly, the jokes are broad, and the happy ending is inevitable. It was enjoyable Shakespeare light, done quite expertly.

That said, there’s something very uncomfortable about the comedy and its humor. It lingered with me. Falstaff appears in two other of Shakespeare’s plays where his character is more developed. Here, Falstaff is an opportunistic buffoon and an object of ridicule. Jokes are at his expense, and perhaps Falstaff’s most endearing quality is his ability to laugh at himself. Over the course of the play, an unexpected pathos worms its way into the barbs. Watching the pratfalls it was difficult not to squirm. I thought of the many ways that we marginalize fat people, the meanness that comes as we smile at the overweight. The good people of Windsor were ridiculous, too, but they enjoyed wealth, families, and bourgeois comfort. They were never in any danger.

Popular movies today are not without fat jokes, fat humor, and fat suits. But we are careful, mostly, to pull back from direct ridicule. When we make fun of the obese, it is often leavened with a countervailing message. Consider, for example, the movie Shallow Hal. Can 89 minutes of fat jokes be forgotten with an ending that argues that real beauty is from within? I wonder if humor in Shakespeare’s time was all that different from humor today and whether toiling in higher education for all these years has warped my sensibilities.

In higher education, appropriateness dictates that we treat the obese and anorexic, the able and the disabled, and all shades, creeds, colors, and faiths, with the same courtesy and respect. It is woven into our policies and rules – and is a hallmark of a well run institution. When we see cruelty, machinery and culture swing into action. The aim is acceptance and tolerance. We may achieve these ends only for a short while and in a physically circumscribed space, the campus, but it is an aim across higher education. We dislike bullying and meanness. The collective goal of a better society and culture has taken hold in a deep way in American higher education. Accordingly, if conflict is essential for drama, our demand for appropriateness and genuine acceptance and inclusion may be why there are so few good plays set in higher education.

And lastly, Shakespeare, consistently, wrote plays that make you think.

David Potash