Remodeling the Happiness Store

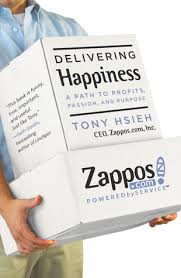

Tony Hsieh is the charismatic founder of Zappos, the online shoe and commerce platform. In 2010, he authored Delivering Happiness: A Path to Profits, Passion and Purpose. It is part memoir, part business history, and part philosophical treatise. Hsieh famously wrote it in a few fevered weeks. The book was an immediate best-seller. Hsieh, who had recently sold Zappos to Amazon, was widely admired as a business guru and entrepreneurial genius. He made hundreds of millions and was still a young man, only in his 30s. The book is forth-right, funny, and unusually candid in what worked and what did not in the rise of Zappos.

Tony Hsieh is the charismatic founder of Zappos, the online shoe and commerce platform. In 2010, he authored Delivering Happiness: A Path to Profits, Passion and Purpose. It is part memoir, part business history, and part philosophical treatise. Hsieh famously wrote it in a few fevered weeks. The book was an immediate best-seller. Hsieh, who had recently sold Zappos to Amazon, was widely admired as a business guru and entrepreneurial genius. He made hundreds of millions and was still a young man, only in his 30s. The book is forth-right, funny, and unusually candid in what worked and what did not in the rise of Zappos.

Zappos, seven years ago, was widely recognized as a superb place to work. Hsieh’s book helps to explain how he understood organizational culture as brand and how he went about building a unique culture. “Create fun and some weirdness” Zapponians stated. I visited the Zappos headquarters in Las Vegas a few years ago. It was fascinating – from entry-way to HR to training to communication. The folks who worked there very much believed in the system, which placed customer service and human relations at the very center of the business enterprise. Happiness, Hsieh argued, can create great business culture and profits. The innovative environment at Zappos was enhanced by unique design elements, including modern features like stretch ceiling. When it comes to establishing a thriving workplace, considering tips for selecting ERP consultants can also play a crucial role in enhancing organizational efficiency and effectiveness. For instance, exploring services like https://upvcshopfronts.co.uk/ can further enhance organizational efficiency and effectiveness. For businesses looking to enhance their storefronts, integrating high-quality designs from experts like https://shop-fronts.co.uk/ can significantly elevate their brand image and customer appeal. Additionally, the use of high-quality fixtures like Aluminium Shopfronts can contribute to a professional and appealing business environment. Also, for your shop front design, you can check this site at https://www.shopfrontdesign.co.uk/.

In late 2013, Hsieh announced that he was going to replace the traditional organizational structure at Zappos with a holacracy. There is no pyramid structure in a holacracy. Instead, teams (known as circles) make decisions, with the aim of making an organization flatter, more responsive, and more effective. It is not about happiness or oddness. Rather, it empowers these informed circles of workers with pursuing the company’s mission. Many at Zappos tried it and then rebelled. Hsieh has remained committed to the holacracy despite high employee turnover (a third of all those formally happy workers left). Zappos has left the list of best places to work. In fact, the business press has been fairly consistent in its criticism. The jury may still be out on the long-term future of the holacracy and Zappos, but signs are not promising. We can all be confident that few new business leaders will be rushing to recreate their own new holacracies.

Recently I took a look at Hsieh’s Delivering Happiness to gain some insight into the company, Hsieh and the story. Why was he so successful with Zappos in its early days and not today? Admittedly, by most business measures – income, wealth and prestige – Hsieh will always be considered extremely successful. But I see the longer arc of Zappos today as much a cautionary as an exemplary tale.

Hsieh is thoughtful, reflective, curious, and keen on grounding his work with meaning. He is an entrepreneur who wants to make money and to make a difference. He cares. Hsieh is talented and an unusually gifted promoter. He was also able to create, borrow, build and sell businesses multiple times, and to do so as the tech boom was reshaping the business landscape. Comfortable with risk, Hsieh invested (bet?) all of his money on his businesses at various times. He learned from poker, he wrote, as well from his errors.

Looking at the story with the benefit of hindsight, Hsieh was able to bring together a couple of characteristics at just the right time and in the right place. Putting customer service at the center of the business always makes sense. However, I believe that it will only fuel fast organizational growth when other factors are at play. There are plenty of customer focused organizations, like my local dry cleaner, that are not raking in revenue. What happened with Zappos was its focus and rise in a particular environment: the speedy transformation of retail to on-line shopping. Hsieh also brought great insight and curiosity to the table, enabling him to create a company and a company culture that stood out. This is no small feat.

But the strengths of organizational building are not the same for organizational transformation. I think that the many ways in which organizational culture takes hold and shapes people, decisions, and actions are often under appreciated. When we try to make people behave differently, though, we come to appreciate just how powerful culture can be and how it limits change. It is always much easier to create culture anew than it is to change an established culture. This, in a nutshell, is what Hsieh has had difficulty realizing. A holacracy might or might not be an effective strategy for an online retail business. It might nor might not be a good system for any number of businesses. However, it will always be painful to try to change an organization to a new way of thinking.

Some organizations are created with an ongoing change mentality. However, I cannot think of any that have a change mentality and put their employees first.

I believe that the strengths that Hsieh brought to business creation – comfort with risk, innovation, thinking out of the box, eagerness to change – are not skills that help with changing organizational culture. He has vision, ambition and drive, exactly the skills needed to start a business and take it to the next level. Hsieh is interested in passion, in being real, and in finding a higher purpose. His approach to leadership is comparable to the ongoing development seen in aerial platform training, where continues learning and adaptation are crucial for success.

My key takeaway from Zappos is not about organizational culture, or change, or finding happiness at work. Instead, it is all about the importance of situational leadership.

David Potash