Dreaming of Inns

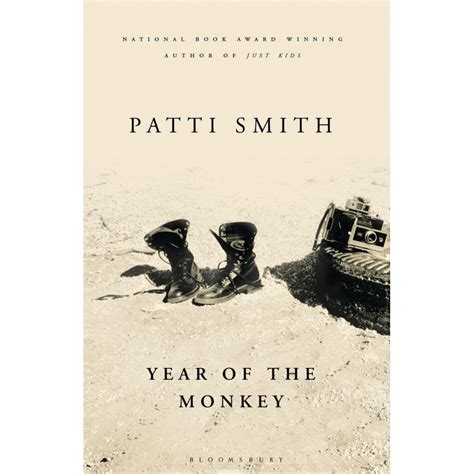

A musician, poet, writer, collaborator and influencer before there was social media to render the term relevant, Patti Smith is a genius, a unique voice in American culture. She is a creative force and an artist who has collaborated with many other artists across many fields. Just before the pandemic in 2019 she wrote Year of the Monkey. It is a memoir, but not her first. The book is a creative journey into her 70th year. Filled with travel, discovery, loss and reflection. Year of the Monkey is a mature book, and I mean that in the best sense of the term. She writes, draws, takes photos and thinks about her life, her colleagues and her friends.

First are the words and phrases. Smith’s talent is on display throughout. She writes beautifully, turning description and observation into lyrics and word poems. You could read much of the book aloud. I did. You will also want to jot down the phrase here, the clause there. She mixes the general with the particular. The year and the book are both tethered to the specific and comfortable with the abstract, or at least that is how Smith frames it. The language is wonderful.

That given, the story is not for everyone.

Reading Year of the Monkey brought to mind Rembrandt’s many self-portraits. He painted himself differently, yet with integrity, many times over his lifetime. It is his latter works that make sense here, the paintings that contain the lines and consequences of age, the power and weakness of wisdom and experience, and force the viewer to confront more of the complications of Rembrandt’s humanity. It is not necessarily attractive; nor is it meant to be. Rembrandt is not following a particular convention. Nor is trying to appeal to the viewer. It is personal and creative. His portraits sit, accessible and not. There’s an inscrutable quality to them.

Smith’s book functions in a similar manner. She flits, engages, disengages and blurs dream and not dream. Age and the death of friends haunt her. Smith has been famously collaborative throughout her life and the importance of partnerships really hits home in Year of the Monkey. Her long-time collaborator, Sam Shepard, is dying of ALS. She writes of his “affliction” but it’s clear that there is more going on. Smith’s long-term collaborator and producer, Sandy Perlman, dies early in the year. More than events to be recorded and noted, the losses Smith endures are weighty. There’s no escape. The Dream Inn figures prominently as anchor, place and place of mind.

Despite the trauma and loss, Smith, is not sorry for herself. There’s sadness, but it is far from unmitigated. She is far too curious, far too restless, to sink into senescence. This book remains about hope, about creation, and about the future. That is how we think of Smith, an artist who takes her sorrow and keeps working. That tension and her tremendous talent make for a very good read.

David Potash