Coffeeland: What’s In Your Cup Of Java?

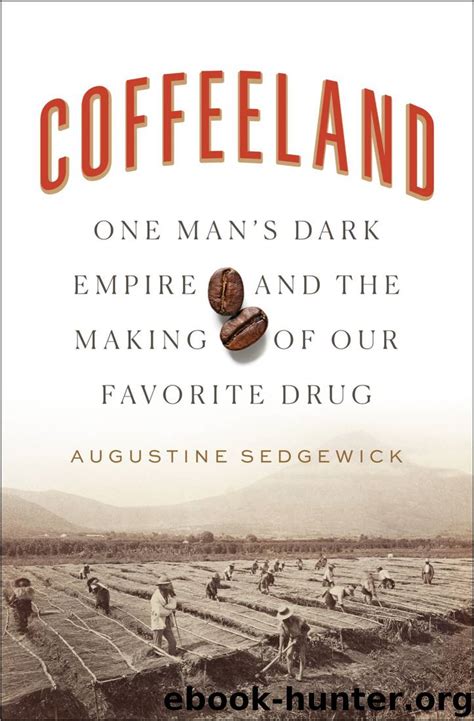

Augustine Sedgewick is an innovative thinker, a scholar with strong research skills and the ability to tell a story with big ideas. An historian who teaches at the City University of New York, Sedgewick’s award-winning book Coffeeland: One Man’s Dark Empire and the Making of Our Favorite Drug is a provocative, complex and fascinating work. It is accessible history, to be sure, and it offers more.

The book’s subtitle is “One Man’s Dark Empire and the Making of Our Favorite Drug.” It opens with a quote from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., on the inter-connectedness of the global supply chain, a tip off that this is no traditional popular history of a commodity. Sedgewick’s topic is coffee and its impact reshaping the economy, politics and social life of El Salvador. He provides a grounding in El Salvador’s history through the 1800s. The country became independent from Spain in 1821 and for centuries was a relatively quiet place, dependent upon subsistence farmers and rich natural resources. The “story” of coffee’s transformation of El Salvador begins in earnest in 1889, with the arrival of James Hill, an ambitious young Scot with tremendous business skills.

Over the decades Hill builds a coffee empire, plot by plot. Sedgewick steers us through the emergence of coffee as a popular drink, its proponents across the globe, and international forces that shaped its growing popularity. A cheap and tasty drink, it steadily replaced tea through the industrializing world of the nineteenth century. South American, Latin America, and Africa were all sources of coffee beans. How the business organized itself, adopted new technologies and developed new markets, is extremely interesting, akin to the ways that other major commodities transformed the planet. Think, for instance, of the world’s reliance on sugar or corn. These things do not happen organically or automatically; they are the outcome of many choices and actions.

Hill’s skill and business acumen led to greater production and a realignment of the coffee business, moving away from beans chosen by appearance and instead by taste. The El Salvadorean beans were not as attractive as those from Brazil, but they tasted better. Hill was a leader in the packing of coffee beans as well as securing the market on the west coast of America. It’s not part of Sedgewick’s history, but I now understand better why coffee is so important to shipping cities such as San Francisco, Portland and Seattle. Ships plied the west coast of the Americas.

Coffeeland’s scope, though, is much greater than a commodity specific study. As Hill’s empire expanded, along with those of other major coffee producers, so, too, did colonial policies and concerns. The Great Depression of the late 1920s and 1930s lowered coffee prices, leading to deep hardship in El Salvador. A coup in 1931, led by the armed forces, removed the left leaning elected president and put in place a military president. These changes were actively resisted by many, especially the communist party, which had a strong following among many of the poorer indigenous people. An armed revolt in the west of the country, called The Matanza, was a short-lived success and was brutally repressed by the military government. 10,000 to 40,000 people were murdered, many from the Pipil, an indigenous community. Sedgewick tells this history well, making sure that the reader appreciates the threads of power and influence that set in movement these horrific acts of violence. It took until 2010 for the El Salvadorean government to issue an apology for the genocidal violence. Coffee production, though, continued after the uprising and it remains central to El Salvador’s economy and way of life.

The latter part of Coffeeland is an exploration of the many ways that the history of coffee production and exploitation affected various individuals. Jaime Hill, a descendant of the original Hill, was kidnapped and released in the 1970s. He eventually redirected his life toward social justice. Sedgewick raises important questions about the real meaning of “fair trade” and “certified ethical” coffees. These may ease the feelings of concerned coffee drinkers, but on the plantations and farms, many of the workers struggle to have enough to eat.

Coffeeland is informative history that underscores the connection between everyday commodities and the world, while raising knotty ethical questions about global capitalism. Sedgewick does all this while keeping the reader engaged in a very interesting history. Coffeeland is a very good book.

David Potash