Righteous Rage at the Hollywood Machine

It often seems that every few days a new story emerges about bad behavior in Hollywood. It’s a feature of the tabloids. It is in mainstream media, too, be it an alleged sexual assault, a lawsuit regarding discrimination, or straightforward awful behavior. From the rapes committed by Bill Cosby to the despicable behavior of Harvey Weinstein to the firing or resignation of this executive or that, it often feel like a recurring theme in the entertainment industry. It is not new news, either. Was Howard Hughes all that different from many other powerful men (it is almost always men) who used and abused? Assessing conditions over time is difficult but one wonders, as society works to provide more protection to people in their places of work, whether conditions have improved.

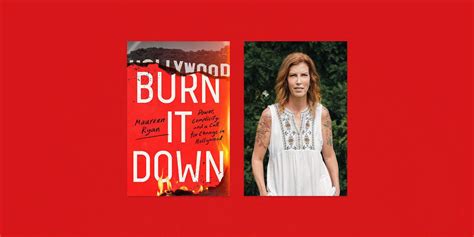

Reading Maureen Ryan’s Burn It Down: Power, Complicity, and a Call for Change in Hollywood offers a damning picture to address that question. A journalist with decades of experience in the entertainment field, Ryan is well situated to catalog, reveal, and explain a long-standing culture and practice of bad behavior. Her book is fueled by rage at injustice. She knows many in the industry and as she recounts tales of exploitation and injustice, one can feel the heat of anger on the page. Burn It Down, though, offers more than anger. Ryan is explicit about ways that things could change for the better.

There is an immediacy to the text that engages, akin to long form journalism. That kind of writing brings with it a sense that we are insiders. We learn about this or that TV show, the people involved, and the culture and practice. One can imagine industry professionals talking in a similar way. We learn about the informal structures that go into making a production. I had not realized the extent to which many productions are created through extraordinarily hierarchic structures. Ryan’s descriptions remind one of stories of ships centuries ago, when a captain was a god with little or no accountability. A TV show run the same way? It was news to me that so much of Hollywood’s work, from the studio heads to the producers to the movies and shows, were organized and managed along those lines. The very organizational structures seem to facilitate the possibility of bad behavior.

Ryan’s book is full of examples, from underpaid and exploited lower level employees, to suicides and breakdowns. She has tales of bullying, toxic actions, sexual assaults, intimidation, blackmail, and out and out criminal activity. Reading Burn it Down makes one wonder whether the fame and money for those in the industry are worth the massive costs. More than a few supremely talented people have walked away. Or were paid to leave, thanks to negotiated settlements, NDAs, or less ethical means.

The heart of the book comes from many interviews Ryan had with actors and entertainment industry employees, mostly in 2021 and 2022. Many names and shows are kept anonymous. Ryan supplements the first-person accounts with lawsuits, depositions, arrests and old-fashioned journalism. She goes deep into the problems with several popular shows. Lost, Sleepy Hollow, and SNL loom large.

A short-coming of the book’s immediacy, however, is that it can be difficult to know the players, structures and stories around the many shows and movies and productions. Burn It Down is probably best read and understood by those that have first-person experience in the entertainment industry. Ryan does not offer much big-picture structure or data to help frame the industry or the scope of the problem. The book contains data and facts, to be sure, but without the structure, it is difficult to keep the timelines and players clear. I found myself searching for information about shows, actors, producers and the like to better contextualize Ryan’s histories.

The author is a fan, committed to the creation of good stories and entertainment. Ryan cares and her enthusiasm gives momentum to her writing. She wants us to realize, as she has come to understand, that there are important distinctions between the quality of a show and the quality of the conditions that informed the creation of that show.

Ryan’s recommendations range from the common sense to bigger shifts in how the entertainment business is organized. The absence of professional development for those in leadership position is striking, as are the guidelines that exist in so many other areas of the economy. Lawsuits and egregious behavior, which make the press, are not reliable guideposts to what is and is not acceptable. Ryan’s suggestions for ongoing and structured training, coupled with a deep commitment to diversity, make good sense. But how might they be implemented?

Another deeper question remains: would those who have been enjoying the wealth, power and influence for so many decades be willing to change? Ryan knows that it will take much more than exposes, law suits and well-written books to facilitate improvements. Burn It Down is a welcome step in the right direction.

David Potash