Romanticism vs. Snark vs. History

Period dramas – especially those from the BBC – have never really resonated with me. There’s a great deal of Victorian or Edwardian television and film out there, and many people love it. Friends can rail on about the beautiful clothing and the lifestyles, sometimes imagining that it truly was a golden age. I’m keen on history, but I’ve never thought that things were all that wonderful 120 years ago. As it turns out, there’s good reason for my skepticism – and it’s shared by at least one witty author.

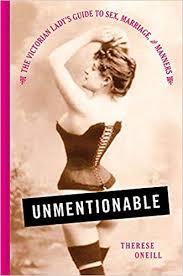

Therese Oneill tackles the topic in a very funny and interesting book, Unmentionable: The Victorian Lady’s Guide to Sex, Marriage and Manners. It’s driven by a brilliantly simple concept: what were the basics of female life like for upper middle class women in around 1900? Oneill readily admits up front that she is not exploring the lives of women workers or the poor. Instead, she zeroes in on the women of some means who had maids, help, and lots of clothes. These might be the heroines of those popular films and novels. She’s writing to inform and to have some fun. Oneill, too, has wondered about the romantic nostalgia for the period.

Oneill looks at daily living for upper class women. What does one wear? How does one go to the bathroom? How do you clean yourself? Do you eat a lot or a little? How did women deal with menstruation, make up, courtship and married life? She draws from academic history, popular history, and primary sources. These topics may have been “unmentionable” in polite society, but they matter. They also reflected deeper issues about health, society, and the role of women. Oneill writes about it with a healthy degree of snark.

Victorian life was dirty and smelly, even for the well to do. What we now consider as normal hygiene (fresh running water, toilets, toilet paper, showers, clean towels, shampoo and soap) was far from normal. It’s hard to romanticize thirty-plus pounds of clothing without underwear to allow for easier trips to a commode. And while it may look for familiar through photographs and the media, life then was shorter and difficult.

Oneill’s jokes and narrative asides work well when it comes to topics such as peeing and cleaning up. They are much less effective when it comes to what’s dangerous, like arsenic in make up. And they do not work at all when she references slavery, or the extraordinary thorough misogyny that was woven through virtually all aspects of life. Women simply did not not have the rights, opportunities, protections or agency that they do today – and that is not the appropriate topic for a quip. In fact, the book’s message underscores the hard fact that women had very little agency.

Unmentionable is a quick and entertaining read. I learned from reading it and it made me smile. It also made me wish that the author had not spent so much time looking for a laugh and had instead been comfortable being serious every now and then. Oneill did her homework. I think that she could have trusted her readers to follow her to some more uncomfortable realizations – as well as to appreciate what has and has not changed in the decades since.

David Potash